The big debate!

At Complete we specialise in the rehabilitation of tendon complaints, both of the upper limb and lower limb. We see hundreds of Achilles tendon complaints across our clinics every year and a significant portion of them are post rupture.

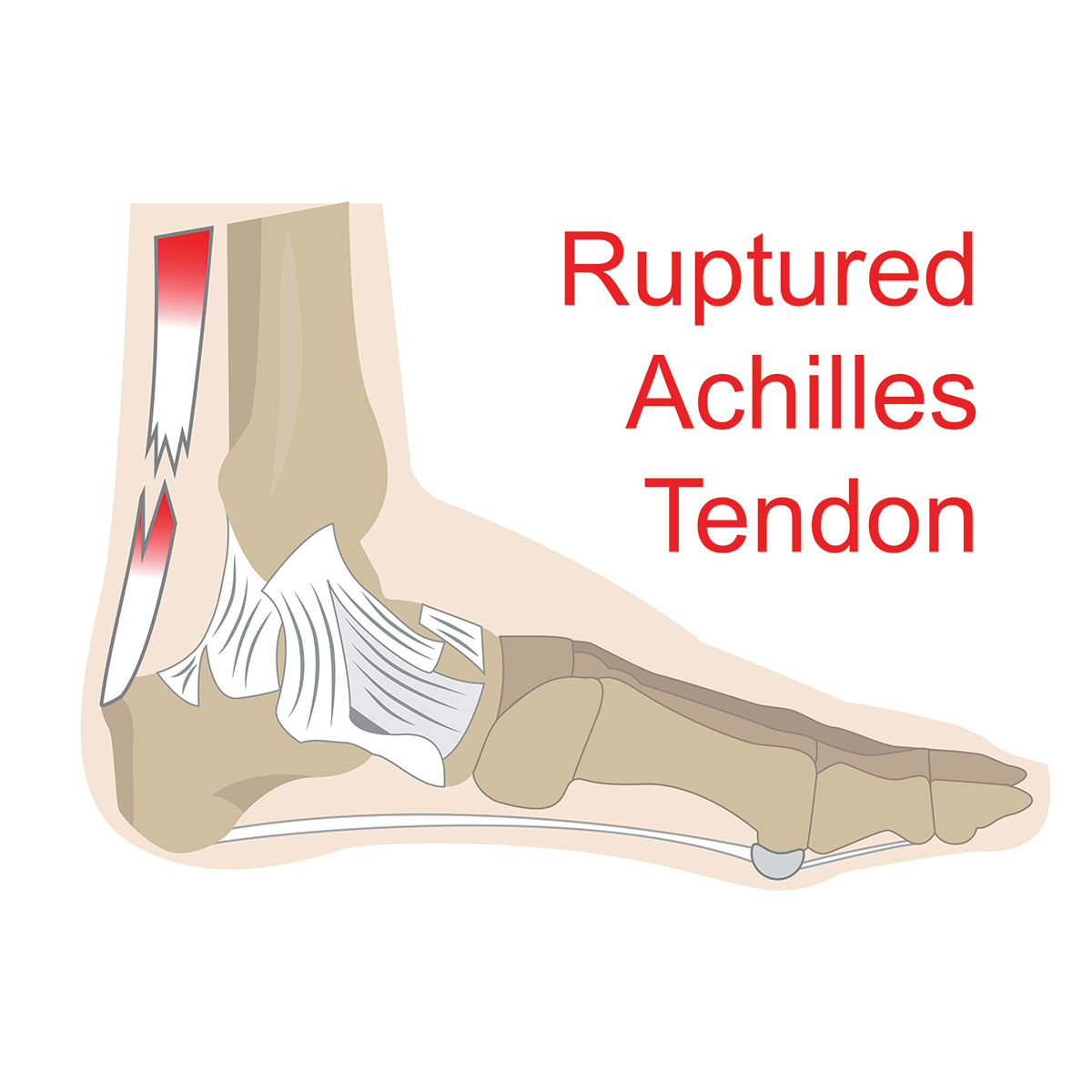

The Achilles tendon is the strongest and thickest tendon in the body, but despite this it is the most common to rupture. The most common region for an Achilles tendon to rupture is in the middle of the tendon (known as the mid-tendon or mid-substance). However, they can also rupture at the attachment to the heel (known as the insertion) and also where the tendon meets the muscle (known as the musculotendinous junction (MTJ). This article discusses the mid-tendon, which is the most common region to rupture.

Interestingly and rather surprisingly, most patients with mid-tendon rupture have no Achilles pain prior to rupture. These ruptures commonly occur in sports with repetitive jumping and sprinting activities, which require a pushing-off type of force.

Diagnosis of Achilles tendon rupture

Patients usually complain of:

- A sudden popping sound or giving way sensation

- Weakness in the foot – unable to lift the foot properly to clear the ground whilst walking

- Immediate acute pain, which often dissipates quickly

The diagnosis of an Achilles tendon rupture requires a comprehensive clinical assessment, including history taking and physical examination (including the Thompson Test), and a diagnostic ultrasound scan. Both of these can be carried out by our clinical specialist physiotherapists at Complete, who are dual trained physiotherapists and MSK sonographers.

Kotnis et al. (2006) recommended dynamic ultrasound as a useful diagnostic tool, noting that if a > 5-mm gap is noted between tendon edges, that surgical intervention is indicated. Some studies and clinics will suggest a > 10mm gap requires surgical input. A dynamic diagnostic ultrasound provides very important information to help ascertain if surgical treatment is required.

The Research

Recent studies have shown an increase in the incidence of Achilles tendon ruptures. This could be related to having a more active older population. Rupture of the Achilles tendon has an incidence of 31 per 100000 per year and is most common in the young to middle-aged active population, with a reported mean age ranging from 37 to 44 years (Egger et al., 2017). It occurs in athletes and non-athletes and is a debilitating condition with a long recovery. The Achilles tendon attaches the calf muscle to the heel bone (calcaneum) and is essential for activities of daily living such as walking, going up and down stairs, and running.

It is not uncommon in professional sports, both men’s and women’s. It is particularly common in male footballers – John Barnes, David Beckham, Callum Hudson-Odoi, Laurent Koscielny and Santi Cazorla to name just a few. All professional footballers will be managed with an operation to bring the two ends of the tendon together. The average time for these footballers to return to sport after a ruptured Achilles is just over 7 months. So why do all footballers have the operation but not everyone? There are many factors to consider, which will be outlined in this article.

Management options

There are many factors for the clinician and patient to consider when deciding if a patient has a surgical repair or is conservatively managed in a ‘walking boot’, also known as the ‘Beckham Boot’ (see image below).

Non–operative (conservative) versus surgical management

A decade ago, surgical treatment was often favoured for an Achilles rupture due to the concerns related to re-rupture rate with conservative (non-operative management). Kahn et al. (2002) discovered a re-rupture rate of 12.6% in those managed conservatively (without an operation) compared to 3.5% in those who had an operation.

It is important to acknowledge the difference was reported in studies that emphasised traditional immobilisation methods in the conservative method. This means immobilisation with non-weightbearing in a plaster cast for at least six weeks, followed by activity and physiotherapy. Certainly, the re-rupture rate for non-operative management can be lower when there are early functional rehabilitation protocols. We will discuss this more later.

However, more recently (in the last 10 years particularly), there have been many large, well-controlled, randomised controlled studies that have shown the same results for surgical versus conservative (non-surgical) management. As a result, there has been a shift away from surgical management.

Surgical Repair

The incidence of operations following an Achilles rupture has reduced over the past decade as a result of many high-quality trials showing comparable results between operative and non-operative treatment (Ganestam et al., 2016; Egger et al., 2017).

It is worth noting that in elite sport the trend is still to operate as previous studies have demonstrated these athletes return to full capacity faster than those treated with non-surgical options. More recent research does not support this claim.

Surgical repair of an Achilles rupture uses either an open, a mini open or a minimally invasive surgical (MIS) approach. This reflects how big the incision is; an open operation has the largest incision and therefore scar, but provides the best visualisation of the tendon for the surgeon.

It is unknown what provides the best repair. There are multiple randomised control trials which have compared the three methods but have shown conflicting results regarding superiority and complications.

The review by McMahon et al. (2011) is considered to be a well powered study demonstrating that minimally invasive surgery (MIS) had no difference in re-rupture rate, sural nerve injury, deep infection, blood clots (deep vein thrombosis – DVT), or adhesions compared to open repair. The major difference in MIS is a lower rate of superficial infections compared with open repair. Superficial infections effect the skin and do not cause any long term issues, but can be uncomfortable, inconvenient and can delay your rehabilitation. Interestingly, those treated with MIS were approximately three times more likely to report a good or excellent result.

When assessing the mechanical properties of the repair, Clanton et al. (2015) compared open repair with three different MIS repairs on cadaveric tendons. With cyclic loads the MIS tendons were more likely to elongate i.e., get longer (this can potentially cause weakening of the tendon). However, the ultimate failure point i.e., the ultimate strength of the repaired tendons, was the same for all types of repair.

The authors concluded the MIS tendon may need a longer period of protection post- surgery; however, this is unlikely to delay recovery.

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) recommends that surgical repair should be carefully considered in diabetics, smokers, those over 65 years old, the sedentary, the obese and those with a concern surrounding wound healing.

Non–operative (conservative) management

There are two main options for conservative management of the rupture of the mid-Achilles:

- ‘Cast Immobilisation’ for 4 weeks followed by a walking boot for 4 weeks. This is the more traditional method.

- ‘Functional bracing’ (walking boot with wedges) and early rehabilitation over 6-8 weeks.

Both methods are complimented by formal physiotherapy to restore full function. At Complete Physio the majority of our patients are managed this way.

In one study 140 patients were treated with cast immobilisation and found that 86% had an ‘excellent’ or ‘good’ result (Wallace et al., 2004). However, functional bracing (using a walking boot) with wedges, to gradually reduce the amount of plantarflexion i.e., how much the foot is pointing down in the boot, over 6-8 weeks is preferred by patients to cast immobilisation, with earlier return to activity and lower re-rupture rates.

Furthermore, patients who immediately started fully weight bearing i.e., putting as much weight through the injured foot as pain allows, had no difference in outcome scores or return to sport to those who were immobilised and non-weight bearing. Those that engage in an accelerated functional rehabilitation programme, which involved patients beginning range of movement exercises immediately was associated with less tendon lengthening and a quicker return to running (Porter et al., 2015). At Complete we adopt an accelerated functional rehabilitation programme and have found this gets patients back to full function safely and effectively.

Conservative treatment avoids the potential risks of surgery, is a far cheaper option, and there is significant evidence that the outcomes are similar.

Outcomes following Achilles rupture

A review of 108 research studies (Zellers et al., 2016) in the British Journal of Sports Medicine (BJSM) showed that 80% of patients were able to return to their desired function and sport after an acute Achilles rupture. The mean time to return to sport was 6 months, but there was a large range from 2.9 to 10.4 months.

Increasing age and a higher body mass index (BMI) were found to be a strong predictor of a poorer outcome with decreased function and more symptoms at one year (Olsson et al., 2011).

Despite the vast majority of patients returning to sports it has been observed that functional deficits exist, for example reduced calf strength and reduced activity levels continue for 2 years after an acute Achilles rupture. This was the same for both surgical and conservative treatment.

Of note, there were few improvements in function and activity levels between year one and year two after an Achilles rupture. This indicates that the first year is essential in recovering from this injury. Physiotherapy is essential to make the required strength and functional improvements following an Achilles rupture.

One study demonstrated these deficits are still present 10 years after surgical repair for an Achilles tendon rupture (Horstmann et al., 2012). Despite this, patients appear to adapt to these functional deficits as most (8 in 10 patients) return to sport.

If an elite athlete e.g., a professional footballer ruptured their Achilles today, they would have a surgical repair. Why is this the case if the evidence does not favour one option over the other? Trends and cultures do effect decision making in medicine, like any other industry and decisions are not always made on hard science. The beliefs of the individual, the medical team of the club, the surgeon and even their agent can influence the decision. There is also some retrospective data on very active military recruits, that the surgical management group resulted in a return to full function 1.5 months before the non-surgical group and had less associated muscle weakness (Renninger et al., 2016). However, this study was retrospective and should be considered with caution.

But even elite athletes can struggle to return to full function following surgical repair for an Achilles rupture. In the National Basketball Association (NBA), Amin et al. (2013) showed that 39% of players who suffered an Achilles rupture and underwent surgical repair from 1988 to 2011 were unable to return to play in the NBA. Those who were able to play following this injury were found to have a reduction in playing time and performance.

Conclusion

In conclusion, debate still exists as to the best management options for mid-portion Achilles tendon rupture.

Recent large trials have consistently demonstrated that non-surgical (conservative) treatment with early functional rehabilitation results in acceptable outcome and thus is an effective treatment option. This avoids the potential unwanted side effects of surgical intervention, such as infection. There is no significant difference in re-rupture rate between operative and non-operative management in the literature. Of note in elite sport and very active individuals there is often still a tendency to carry out an operation to repair the tendon.

Whether you have surgery or not is dependent on having an open, honest conversation with your surgeon or clinician regards the pros and cons of each treatment option.

At Complete Physio we are very experienced in the management of Achilles tendon ruptures whether you have a surgical repair or are managed conservatively in a walking boot. We will work closely with your orthopaedic consultant to ensure you return to activities of daily living and sport in a safe and timely fashion.

Whether you have had a surgical repair or conservative management of your Achilles rupture – watch this video for top tips for your rehabilitation:

References:

Don’t let pain hold you back, book now!