If you are a regular runner, no doubt someone at some point has said to you that running is bad for your knees. More than likely, it was a non-runner. But there is plenty of evidence to say that the benefits of running far outweigh the risks, and that includes the effect on your knees.

Running is certainly not for everyone, but it is one of the most popular exercise activities and has many associated health benefits. It is a simple, low cost form of exercise that requires little equipment other than a good quality pair of running shoes and appropriate clothing. It is time efficient, easily fitting into a busy schedule, and can be very liberating. Speak to an avid runner and they will likely tell you that life would not be worth living without it.

When people say that running is bad for your knees, they are generally referring to its potential role in the development of OA (osteoarthritis). Running is often considered a cause of knee OA, both by the public and some healthcare practitioners. For the keen runner, this might be a cause for concern. However, it might actually be the case that knee OA is more common in non-runners!

What is OA (osteoarthritis) and what causes it?

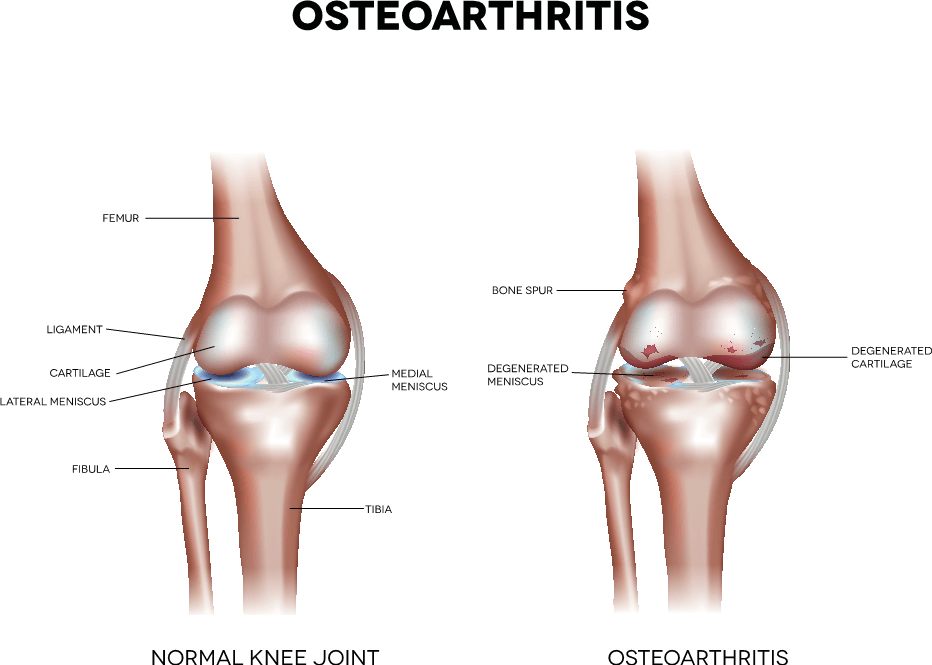

In simple terms, osteoarthritis is when the cartilage (the smooth cushioning tissue) on either side of the joint breaks down. It is often called ‘wear and tear’ or degeneration of the joint surfaces. This is depicted in the image below.

The exact cause is unknown but there are many factors that are thought to contribute to the development of osteoarthritis. Some of these factors you can do nothing about. Fortunately, there are others that you can control.

What you will clearly see from the list below is that there are a large number of risk factors for OA that have absolutely nothing to do with running……….…yet running often takes the blame!

Non-modifiable risk factors

- Age: no surprises here, the risk of developing OA increases with age.

- Sex: females have an increased risk of developing lower limb OA, particularly in the knees.

- Genetics: genetic factors are estimated to account for up to 40% of knee OA (blame your parents!).

- Previous injury: this is one of the most significant risk factors for subsequent development of OA in runners, particularly ACL (anterior cruciate ligament) and meniscal injuries.

Modifiable risk factors

- Weight: obesity is considered one of the primary drivers for developing OA.

- Poor biomechanics: many biomechanical factors are suspected to contribute to the development of OA.

- Sports participation: there will naturally be greater loads on the knee and a higher risk of injury.

- Heavy occupational load / heavy physical work (e.g. farming, military, construction) is associated with an increased incidence of knee OA.

- Weakness: strong muscles are required to control and absorb forces going through the knee joint.

What does the literature say about running and OA knee?

So, what of the advice that “running is bad for your knees”, or “you will wear your knees out if you don’t stop running”?

It has been suggested that repetitive joint loading leads to swelling in the cartilage and disrupts the collagen structure, indicative of early osteoarthritic changes. However, recent literature has described many potential beneficial effects on cartilage from joint loading, including the suppression of inflammation and a reduction in degenerative changes within tissue, as well as improved cartilage structure secondary to joint remodelling in response to the cyclical loading while running (Kenyon et al., 2019). Another positive aspect of running is that it can improve other aspects of the joint such as soft tissue extensibility, blood flow, and synovial fluid mobility. Appropriately dosed running also improves joint proprioception and the strength of supportive hip and knee muscles which will help protect the joint by dispersing forces.

There is also research that shows both excessive loads (high-volume running), as well as insufficient loads (sedentary), can have negative effects on joint cartilage, compared to those engaging in light to moderate levels of running (Castillo et al., 2019). A systematic review looking at the association of recreational and competitive running with knee and hip osteoarthritis (Alentorn-Geli et al., 2017) suggests that the difference in outcomes depends on the frequency and intensity of running. The review involved 25 studies including 125810 people and concluded that only 3.5% of recreational runners had hip or knee arthritis (similar for both male and female runners), whilst sedentary, non-runners (10.2%) and elite, ex-elite, or professional level runners (13.3%) had higher rates of knee and hip arthritis.

So, does running cause knee osteoarthritis? There is no increased risk in running simply for fitness or recreational purposes, and this level of activity provides a wide range of long-term health benefits. However, there seems to be a small risk for knee OA in high-volume, high-intensity runners. Timmins et al. (2016), in their systematic review, concluded they could not find strong evidence for or against running as a cause of knee OA.

Further research is required to separate previously knee-injured subjects from non-knee-injured subjects, consider the role of genetics/epigenetics in runners and non-runners developing knee OA, and also the knee joint ‘chemical’ environment before and after running at varying intensities (Roberts, 2017).

Can/should I continue or take up running?

You decide.

- Recreational runners had less chance of developing knee arthritis compared to sedentary individuals and competitive runners.

- Running at a recreational level for many years (up to 15 years and possibly more) can be safely recommended as a general health exercise, and benefits knee joint health.

- The rate of OA increases if you are sedentary or if you are a high-volume high intensity runner (more than 57 miles per week), compared with regular recreational running.

- The beneficial effects of running on general health are well established and include improved cardiovascular health, diabetic control, mental health, bone mineral density, reduced weight, potential increases in pain threshold, and balance.

In summary, the benefits of running are numerous, and the evidence suggests that you can be confident that recreational running will not harm, and may even improve, your knee joint health.

What measures can I take to protect my knees?

- Wear appropriate, good quality running shoes.

- Increase distance gradually particularly if you are a new runner.

- Make sure you have sufficient recovery time between runs – avoid running on consecutive days (space runs even further apart if necessary).

- Include focused strength training and flexibility in your exercise schedule.

- Cross train – throw in some cycling and Pilates.

- Maintain good general health – good nutrition, sufficient sleep, a BMI between 18.5 and 24.9, and reduce overall stress (easier said than done these days……..but running will certainly help!)

How can a physiotherapist help me?

If you want to run but are concerned about the risk of OA, a physiotherapist can assess for factors that might put you more at risk and discuss the pros and cons of running for you as an individual. They can help develop a specific plan and strategies to help you prevent injury, such as strength and conditioning programmes, or loosening stiff joints and muscles, and they can help to appropriately rehabilitate injuries when they do occur.

If you have any specific questions or would like to speak to or see a physiotherapist about running (or any other activity) and OA knees, please call us on 020 7482 3875 or email info@complete-physio.co.uk

Don’t let pain hold you back, book now!